Santiago de Compostela Rail Disaster (2013)

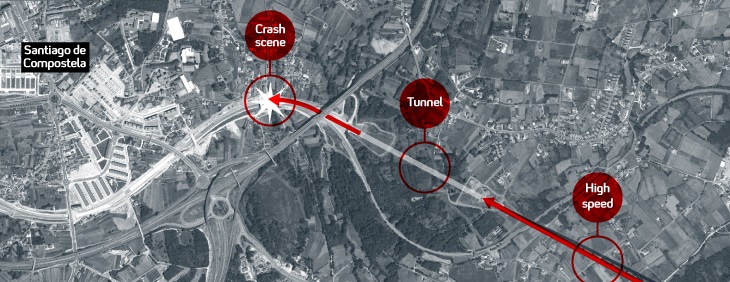

The Santiago de Compostela rail disaster occurred on 24 July 2013, when an Alvia high-speed train travelling from Madrid to Ferrol, in the north-west of Spain, derailed at high speed on a bend about 4 kilometres outside of the railway station at Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Of the 222 people (218 passengers and 4 crew) aboard, around 140 were injured and 79 died.

The train’s data recorder showed that it was travelling at about twice the posted speed limit of 80 kilometres per hour when it entered a bend in the line. The crash was recorded on a track-side camera which shows all thirteen vehicles derailing and four overturning. On 28 July 2013, the train’s driver Francisco José Garzón Amo was charged with 79 counts of homicide by professional recklessness and an undetermined number of counts of causing injury by professional recklessness.

Backgrounds

The Olmedo-Zamora-Galicia high-speed rail line is only partially completed, with some sections of the HSR already in service while other sections still remain as a conventional railway line.

The RENFE Class 730 passenger train is in service on this line, as it can run on both conventional and high-speed tracks. It also has two generator cars that allow its electric traction motors to function on non-electrified lines. It is essentially a hybrid system. It has a top speed of 180 kilometres per hour (110 mph) when running in diesel mode, and around 260 kilometres per hour (160 mph) when running on overhead electrification.

Derailment

At 20:41 CEST (18:41 UTC) on 24 July 2013 the passenger train, on an express route from Madrid Chamartín railway station to Ferrol, derailed on a section of conventional track at the end of the Olmedo-Zamora-Galicia line, at Angrois in Santiago de Compostela. All vehicles, the two power cars, their adjacent generator cars – both with diesel tanks – at both ends of the train and the nine intermediate carriages, derailed as the train rounded the A Grandeira curve; four cars overturned. A track-side CCTV camera video indicates that the front generator car was the first to leave the rails, followed by the leading passenger coaches, the front power car, the rear generator car and finally the rear power car. The train was carrying 218 passengers at the time of the crash. Three of the carriages were torn apart in the accident and another caught fire due to gaseous leaking diesel fuel. The rear generator car also caught fire. Unofficial technical reports disclose that the train was travelling at over twice the posted speed limit when it entered the curve.

Of the 218 passengers, there were 79 fatalities (at one point reported as 80 due to a misidentification of some body parts) and the remaining 139 were injured. Among the dead were foreigners: 1 French, 1 Algerian, 1 Brazilian, 2 Italians, 1 Mexican, 1 Dominican, and 1 American. The train’s two drivers were injured but survived. On 25 July, 36 of the injured were still listed as being in a serious condition.

Investigation

The Comisión de Investigación de Accidentes Ferroviarios is responsible for the investigation of railway accidents in Spain. Núñez Feijóo said it was too early to determine the cause of the accident. A government spokesperson said that all signs pointed to the Santiago de Compostela derailment being an accident and said there was no evidence that terrorism was a factor. Sabotage was also ruled out.

Eyewitnesses said the train was travelling at high speed before derailing which was subsequently confirmed. Data from the train’s black box revealed that 250 m (820 ft) before the start of the curve the train was travelling at 195 km/h (121 mph) and in spite of the emergency brakes being applied was still travelling at 179 km/h (111 mph) when it derailed 4 seconds later. That confirmed a statement made in court by the driver, Garzón Amo, that the train was travelling at 180–190 km/h (111-118 mph) at the time of the accident. That was more than double the speed limit for that curve, which is 80 km/h (50 mph).

The bend where the accident happened is the first curve reached by a Santiago-bound train coming from Ourense after an 80-kilometre (50 mi) stretch of high-speed track which is limited to 200 km/h (124 mph). The high-speed track has ERTMS-compliant signalling, which is designed to slow or stop a train whose driver is ignoring signals or the speed limits. However, the new high-speed line joins a conventional track shared with low-speed trains, at the curve where the accident happened. The conventional track only had the older ASFA signalling system, which will warn drivers if they are exceeding speed limits, but will not automatically slow or stop a speeding train. There is a different system capable of stopping a train if it passes a red signal but that was irrelevant in this case. Part of the ongoing investigation into the incident will focus on whether any of these speed monitoring systems failed. However, the corrective actions taken after the accident indicate that the system as designed did not automatically regulate the train speed to a lower value on leaving the high-speed section.

Court investigators said that the driver was speaking on the telephone to staff at Renfe about the route to Ferrol, and consulting a map or document, shortly before the brakes were activated and that he did apply the brakes, but not in time to achieve the safe speed limit for the curve.

Corrective actions

In the immediate aftermath of the accident, the Spanish rail authority Adif installed three ASFA (“Automatic Braking and Announcement of Signals” in English) balises on 1.9 km of the approach to Santiago de Compostela to enforce speed limits of 160, 60 and 30 km/h, to prevent trains from reaching the 2013 accident point at a speed that would cause a similar derailment. Balises are track-mounted programmable transponders which communicate with the on-board computers on Spanish high-speed trains, and which can cause an automatic brake application if speed restrictions are not obeyed.

Video:

Source: wikipedia.com; channel4.com